Of all the opportunities in the world, the chance to be the first and only person to achieve something is often an experience very few people will have in their lifetime. For John Berry, that is exactly what he has the honour of claiming, as one of the first and only undergraduate Thouron Scholars. With a full life of academic achievements, falling in love, finding new passions, and honest reflection about coming-of-age, John Berry is truly an original.

There are very few living Thouron Scholars who have met both Sir John Rupert Thouron and Lady Esther du Pont Thouron and that is another honour John holds. “I was one of the only two undergraduates ever, and Sir John and his wife rather over-awed me,” says John.

John was the first recipient of the Thouron Award in 1960 and arrived at the University of Pennsylvania to study geology and anthropology. In 1961 he was joined by Peter Prince, one of the only other undergraduate Scholars in the history of the Thouron Award.

It was both an intellectually curious and coming-of-age time for John, who was a young boy venturing off from home in a different country. “The sudden release from the British world of strict social convention and school discipline led to a boisterous and 120% immersion in the life of Penn,” John shares.

A world of privileges abound as a Thouron Scholar

The opportunity not only to grow academically but as a young man was not lost on John. It was a cornerstone in his decision to apply for the Thouron Award. “I was a ‘square peg in a round hole’ in the UK. I was interested in archaeology, history — especially early Medieval, planning, geology, geography, architecture, modern languages [and] I had acceptance to study Natural Science at King’s London and Liverpool University,” recalls John.

However, he didn’t receive acceptance to his top choice programmes, Natural Science or Anglo-Saxon Tripos at Cambridge. It was his mother who urged him to apply for the Thouron Award once she saw an advertisement about the fellowship programme. “I didn’t really ‘get’ how to take full advantage of not only Penn but also the privileged position that we held in American Society as well-funded Ivy League students,” says John.

Without the Thouron Award, John would never have had the opportunity to study abroad. It meant more exposure to different cultural norms and beliefs, perspectives and frameworks, and ways of living — which can be complex to process at the age of an undergraduate. “I was very spoiled at Penn. I very much regretted later that I did not accept art history, creative writing, music, [and] economics, as subjects worthy of academic study until my senior year — when it was too late,” John shares.

Instead, he participated in the humanities in other ways, such as being a member of the Philomathean Society, editor of the Pennsylvania Literary Review, and helping to organise Connaissance Lectures on current affairs — which featured famous political leaders like Alvaro Holden Roberto of the National Liberation Front of Angola.

“I [also] acted in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, took a course in Augustan Literature, and was invited by the professor to change my major. I [also] took every course in anthropology that was open to undergraduates as no undergraduate courses in archaeology were available at the time,” John recalls. It was by happenstance that he became a geology major.

Life and love as a young man in America

After completing his bachelor’s degree in geology in 1963, John went on to complete a master’s degree in geology and geophysics at Columbia University in 1966. “I rushed through Penn because I wanted to stay with my British cohort and get a degree in three years. If I had been less competitive [and] more open to opportunities other than a career as a scientist, I would have benefited more from a fourth year at Penn,” John admits.

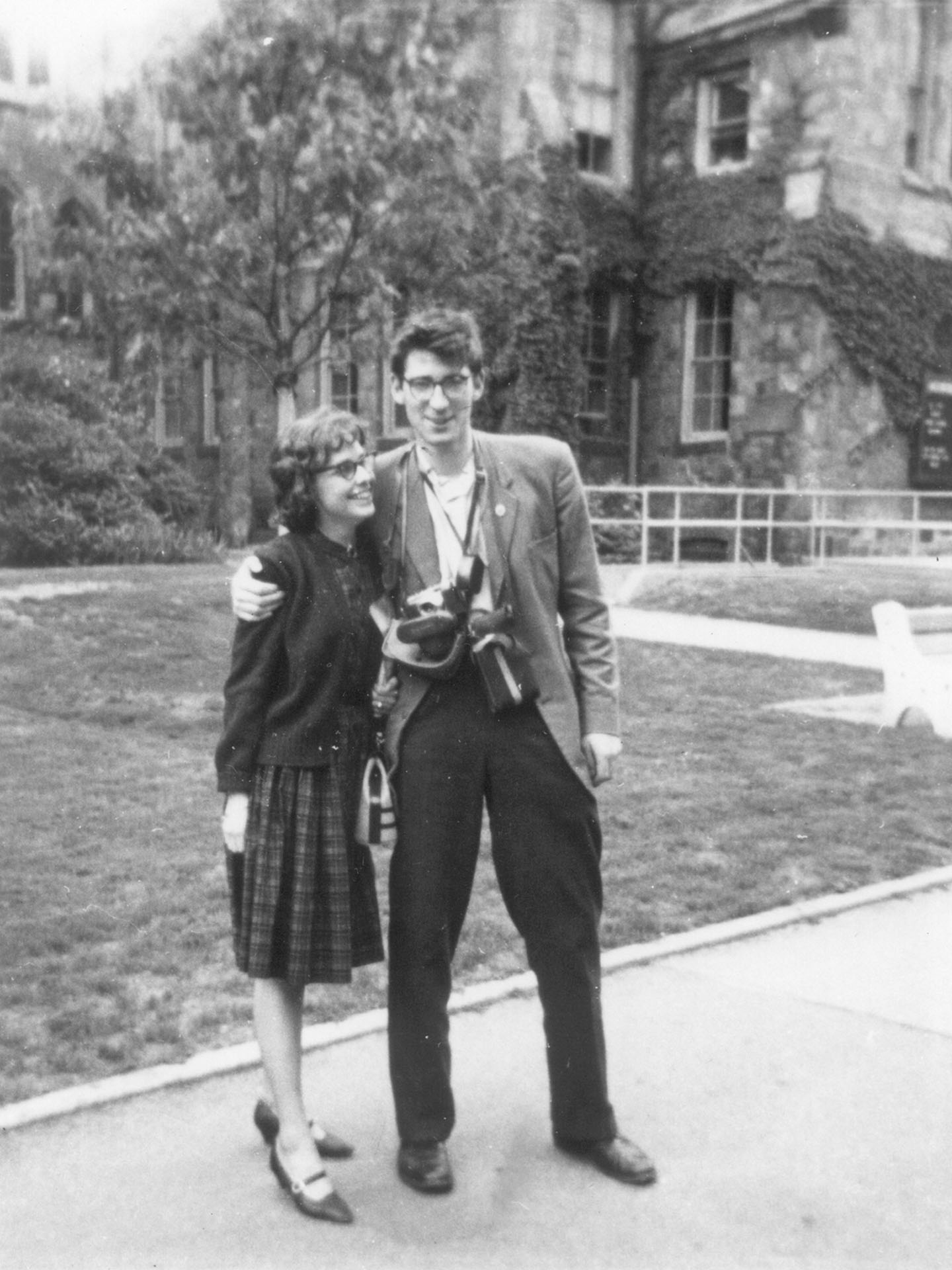

While he would go on to have a rewarding career as a geologist with the Anglo American Corporation, Earth Satellite Corporation, and Shell Oil Company over the span of 30 years, it’s the unexpected gift that the Thouron Award bestowed upon John that he honours the most: two great loves. “I met my late wife, Grace Arlene Burke Jordan, during my senior year at Penn. We immediately fell in love, and I’m still in love with her memory,” shares John.

Grace Arlene was a creative. Her father was Dr. Robert Belle Burke, a classical scholar who translated the Opus Maius of Roger Bacon into English, and that had an impact on her own academic pursuits in creative writing. For 22 years, John and Grace Arlene were married until she passed from a brain tumour that plagued her for the final 13 years of her life.

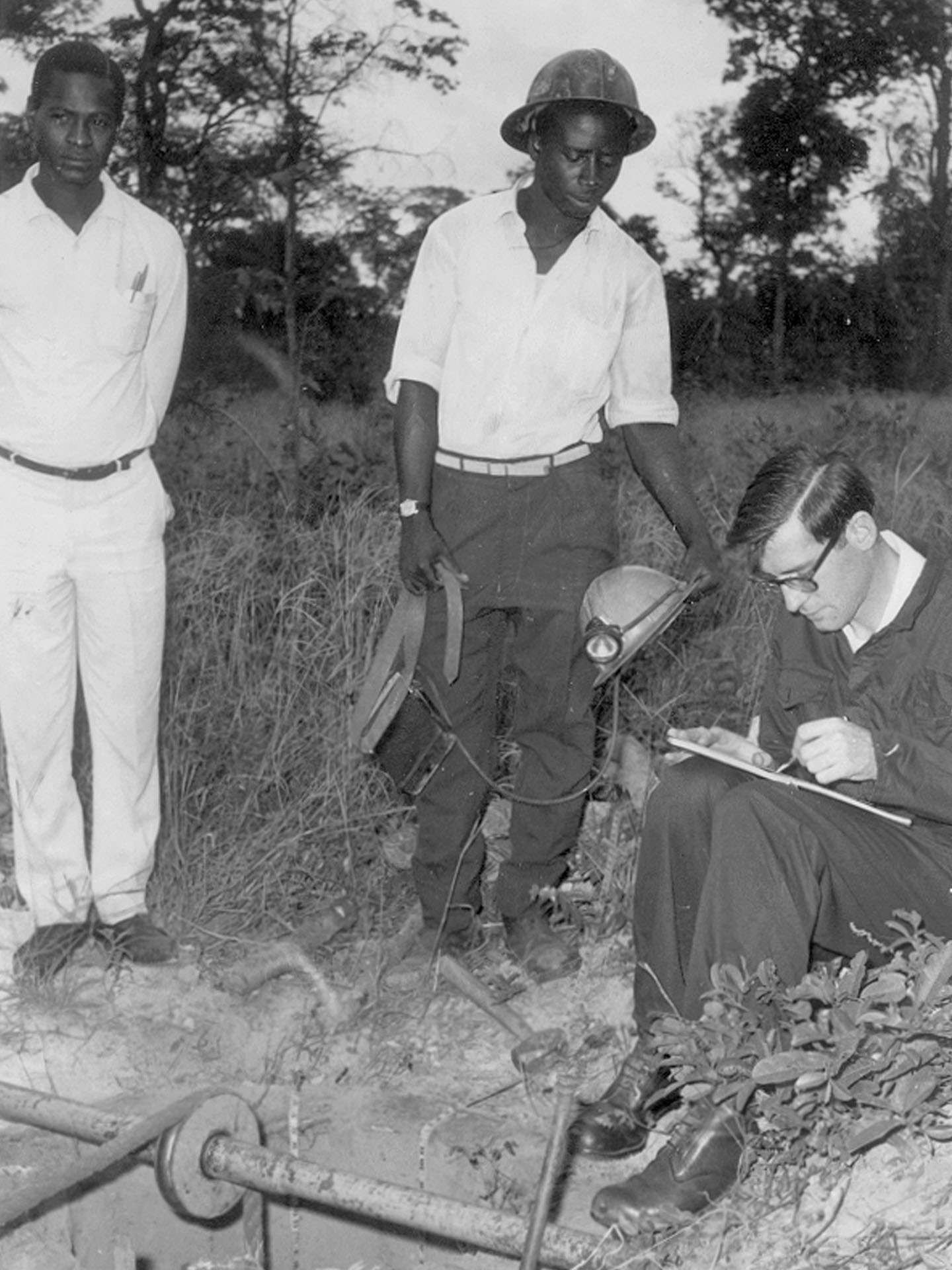

“I went to Africa and might have stayed there except for [Grace Arlene’s] health. I was firmly committed to being a Brit until we returned to the USA because of her health. When she died, Ann Harnwell Ashmead, whom I had met at a Thouron function, introduced me to my present wife,” John explains. And who is that leading lady? None other than Professor Ingrid Elly Maria Edlund-Berry — a classicist and classical archaeologist who studied at Bryn Mawr College.

Of work achievements, John remains proud of his geological career. “At Shell, I developed a way to map natural oil slicks on the surface of the ocean, and to distinguish them from slicks of human origin and from calm patches. I mapped almost every deepwater basin on Earth for slicks, and this resulted in several major off-shore oil discoveries,” John recounts.

An adventurer’s spirit first and foremost

Beyond geology, John’s life has been wonderfully full. In 2015, at the age of 75, he took up sculpting with wood and stone and has never looked back. “I am proud that I have become a sculptor, even though not a great one, at the ripe age of 75. I am [also] proud of having become a choral singer with good choirs, [including Panoramic Voices] — in spite of having been told repeatedly as a young person I was tone deaf,” John jokes.

Through his additional hobbies, such as choir, writing, and futurism, John has found a greater appreciation for elder care and life with the Village movement. “I am active in several committees of the Capitol City Village, [which is a movement] that started in Boston, [and] tries to enable seniors to stay at home until the end,” explains John.

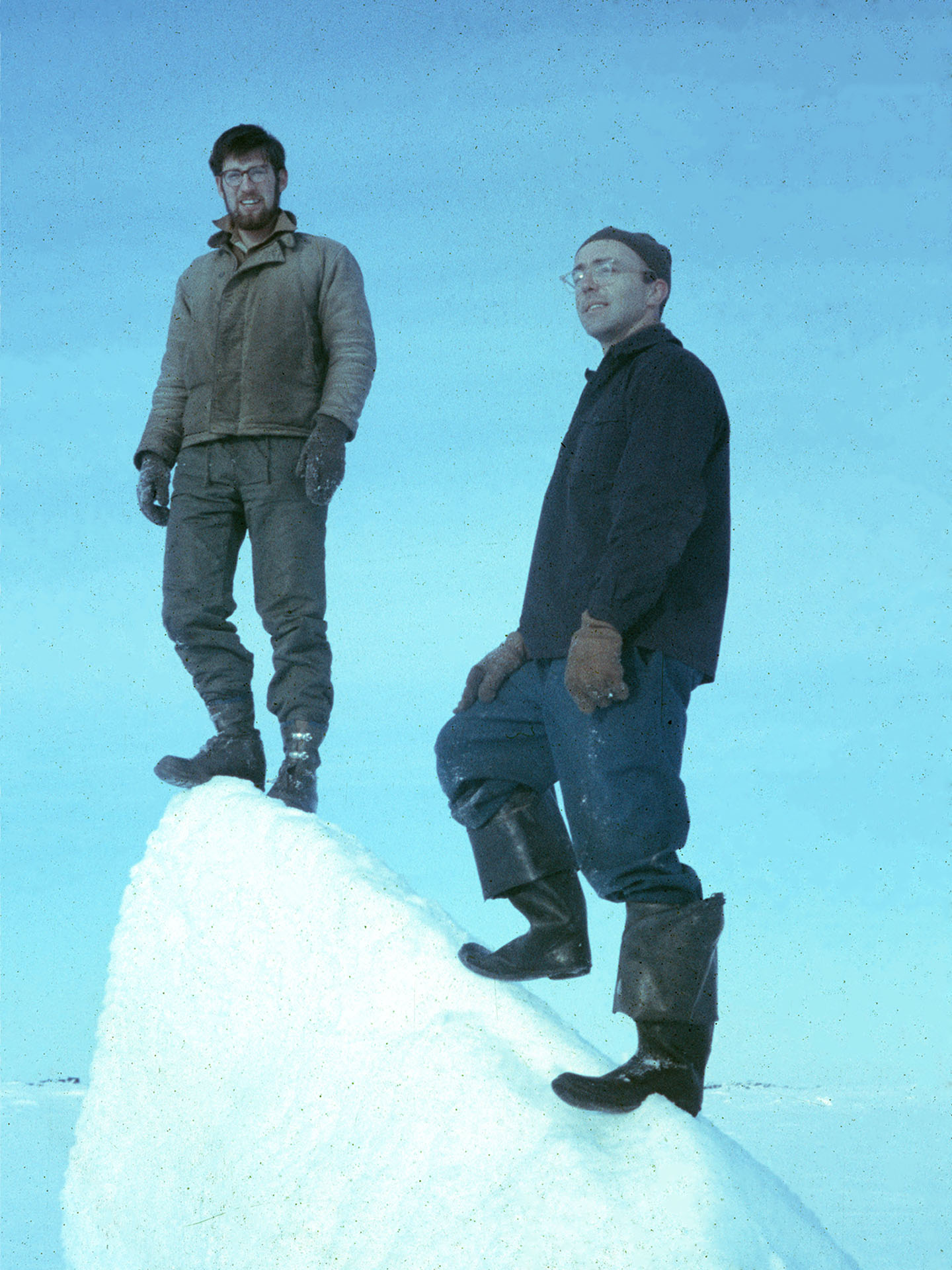

Nonetheless, the adventurer in John is not slowing down for anyone — he has run 13 marathons between the incredible ages of 63 and 75. Most notably, he crossed North America by bicycle from Boca Chica, Texas to Red Bay, Labrador at the age of 62, and then crossed Europe from Swinoujscie, Poland to Tbilisi, Georgia at age 72. “I spend every summer in Europe, riding a folding bicycle around the continent,” John shares.

John also continues with geology as an independent geological consultant in Austin, Texas, and is still publishing work on the topic. “I am on the Board of the Texas Section of American Institute of Professional Geologists. For them, I run a monthly webinar series for continuing education credit — [which] the small fee we charge helps fund our scholarship program,” John details.

A storied pillar in his community, John frequently volunteers with the regional science fair as a judge and the Student Symposium of the Jackson School of Geology at the University of Texas-Austin. It’s a bit serendipitous that much of John’s life present-day is contributing to the cultural and personal development of others. Perhaps that is the sweetest reward of the Thouron Award.

“A large part of [the Thouron] effect on me was to create a desire for adventure, understanding other peoples and their customs, and a willingness to try anything. Hence all the adventures [I have had], and many others,” John laments.

As for the future of the Thouron Award, John genuinely hopes it continues to grow and strengthen as the uniqueness of being directly involved with the Thouron family is something many other fellowships cannot offer young, great minds of our future.

Are you interested in becoming a Thouron Scholar?

Our application cycle for the 2024/2025 academic year will open in July 2023.

Learn more about the Thouron Award — one of the most prestigious and generous academic scholarships in the world.